Back Toskan orderi Azerbaijani Тасканскі ордар Byelorussian Toskanski red BS Ordre toscà Catalan Toskánský řád Czech Toscansk orden Danish Toskanische Ordnung German Τοσκανικός ρυθμός Greek Toskana ordo Esperanto Orden toscano Spanish

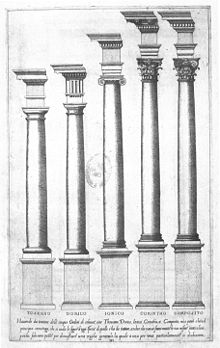

The Tuscan order (Latin Ordo Tuscanicus or Ordo Tuscanus, with the meaning of Etruscan order) is one of the two classical orders developed by the Romans, the other being the composite order. It is influenced by the Doric order, but with un-fluted columns and a simpler entablature with no triglyphs or guttae. While relatively simple columns with round capitals had been part of the vernacular architecture of Italy and much of Europe since at least Etruscan architecture, the Romans did not consider this style to be a distinct architectural order (for example, the Roman architect Vitruvius did not include it alongside his descriptions of the Greek Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders). Its classification as a separate formal order is first mentioned in Isidore of Seville's 6th-century Etymologiae and refined during the Italian Renaissance.[1]

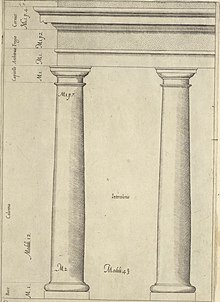

Sebastiano Serlio described five orders including a "Tuscan order", "the solidest and least ornate", in his fourth book[2] of Regole generali di architettura sopra le cinque maniere de gli edifici (1537). Though Fra Giocondo had attempted a first illustration of a Tuscan capital in his printed edition of Vitruvius (1511), he showed the capital with an egg and dart enrichment that belonged to the Ionic. The "most rustic" Tuscan order of Serlio was later carefully delineated by Andrea Palladio.

In its simplicity, the Tuscan order is seen as similar to the Doric order, and yet in its overall proportions, intercolumniation and simpler entablature, it follows the ratios of the Ionic. This strong order was considered most appropriate in military architecture and in docks and warehouses when they were dignified by architectural treatment. Serlio found it "suitable to fortified places, such as city gates, fortresses, castles, treasuries, or where artillery and ammunition are kept, prisons, seaports and other similar structures used in war."

- ^ of Seville, Isidore (2006). The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 312. ISBN 9780521837491.

- ^ The first one published.